“And this, our life, exempt from public haunt, finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything.” –Shakespeare

November 12, 2010

There’s an idea that’s been kicking around in my head for some time, ever since my last post about the Edward Hopper paintings. It’s hard to articulate, but it’s about the importance of place in our psychology, and the degree to which it defines us and gives context to our actions.

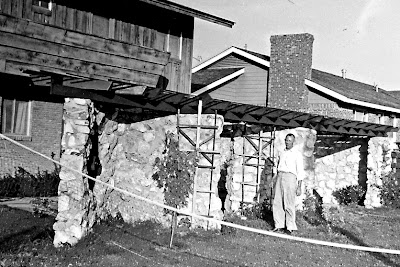

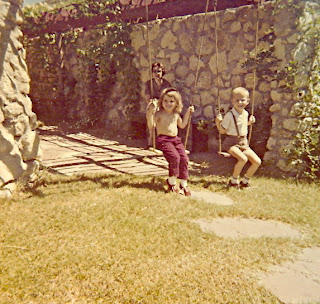

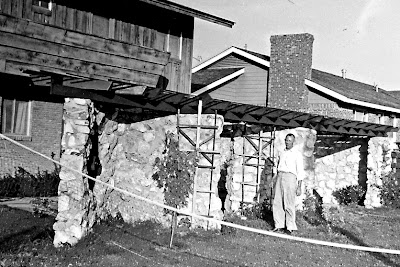

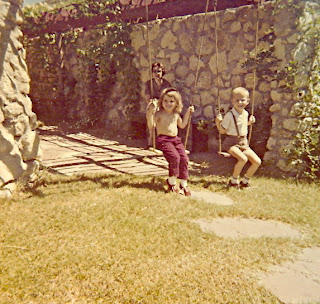

My father Ernest Buckley has been gone for over twenty years. I still dream about him though, and I often dream of the house where I grew up—a house he designed. My dad liked to build things—he was an architect and engineer (he worked in the Civilian Conservation Corp out of high school—there’s a terrific documentary about the CCCs at this link). Our backyard had a series of rock walls that my dad built. Trellises ran along the top of the walls, covered with ivy. On many summer days and evenings, throughout my childhood, I’d lie in a hammock strung between two of these large rock walls, or I’d play in a large stone sandbox that he built for me. Our backyard was the place I felt most myself—the arena of my playing and dreaming.

Now many years later, I frequently find my thoughts going back to my house and my backyard—it lingers in my memory with more specific definition than places I saw just last week. My childhood home defines an ineffable aspect of me that gives meaning to much of my present work (though the house, as we knew it, burned after we moved away. Someone rebuilt it, but it’s no longer the same house—the last time I drove by it I didn’t even recognize it. That thing that defines me no longer exists except in my memory. I have no idea if the rock walls in the backyard are even still standing.)

In his book THE ARCHITECTURE OF HAPPINESS, Alain de Botton writes “There is nothing preternaturally sweet or homespun about the moods embodied in domestic spaces. These spaces can speak to us of the somber as readily as they can of the gentle. There is no necessary connection between the concepts of home and of prettiness; what we call a home is merely any place that succeeds in making more consistently available to us the important truths which the wider world ignores, or which our distracted and irresolute selves have trouble holding on to. As we write, so we build: to keep a record of what matters to us.”

Likewise we create films, to keep a record of what matters to us. And films often create psychological states through the use of place. When I think about any specific film that’s had meaning for me, it’s almost always an image that comes to mind–no matter how clever the dialogue, it is the images that linger, that shape my feelings–and oftentimes it’s the place that the characters inhabit that shape that image, and my psychological response to it.

When Michael Powell’s BLACK NARCISSUS crosses my mind, it’s the image of a nun–dressed in white, standing on the edge of a cliff–that emerges from my memory. It’s an image both pleasing and vertiginous. It evokes for me the themes of the movie—commitment to spiritual principles as a balancing act—the hard rock of principle against the green valley of desire, the struggle of spirit and the flesh, the high and the low. The movie is full of images that make me feel that struggle—tracking shots of a nun moving through a room against a mural of lovers and nude women; the small figures of human beings against the enormity of the mountains around them; dissolves and cuts that capture the nature of memory and loss—a woman, thinking of her youth, in a place she loved, then fighting the memory and the loss it represents.

This is one of the great dissolves in film, concluding Sister Clodagh’s memory of her youth.

The film is a remarkable achievement and it’s the architecture of the film that defines the experience for me. There is symmetry to the compositions, and a density of detail, that reinforce the ideas on a visceral level.

David Kehr wrote beautifully about the film: “Powell builds BLACK NARCISSUS as a series of moods created through space and color. He contrasts the boxy interiors and blank walls of the British colonial offices with the curved, multi-leveled, spatially indefinite chambers of the old palace. British certainty and sterility cedes more and more to Eastern mysticism and sensuality; the sister in charge of the vegetable garden can’t help but plant a crop of flowers instead, their exploding primary colors providing a dizzying contrast with the black and white habits of the nuns. Gentle, green hillsides—reminiscent of the Scottish landscapes we see in Sister Clodagh’s flashbacks—suddenly turn into vertiginous canyons when viewed from another angle. The ground literally opens beneath the feet of the characters, inviting them to take the plunge—to abandon their twin faiths, in God and the British Empire, and turn themselves over to more ancient and dangerous powers.”

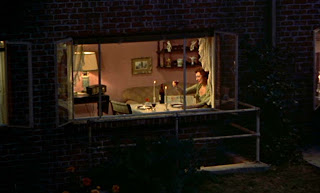

Likewise REAR WINDOW, probably my favorite Hitchcock film, presents me with a visual template that illustrates its themes: a man peers into his neighbors’ apartments, but what he’s really looking at are components of his own consciousness. The hero’s journey is one of introspection: by studying his neighbors, he learns more about himself—his fear of commitment and his frustration with stasis. The suspense story is almost beside the point—it is just the vehicle to present the character’s psychological development.

Each apartment in REAR WINDOW represents some type of relationship, or the lack thereof: newlyweds; an unhappy couple; a woman hotly pursued by many men; a lonely woman who fantasizes about meeting anyone at all; and assorted others. The film is only a murder mystery on the surface. It is actually about the fear of commitment.

The movie has long been a favorite because it captures my own desire to understand what is going on in the external world, and how that reflects back upon my own experience. The courtyard in REAR WINDOW becomes the container for that exploration, the compartmentalizing of my own thoughts about relationships.

Ingmar Bergman’s FANNY AND ALEXANDER similarly affects me by its visual style: Alexander, hiding under a table, imagines that statues move. This reminds me of my own childhood and evokes those feelings—the mystery of hiding in the backyard, or a closet, waiting for the world to reveal itself.

The film explores Alexander’s consciousness with many dreamlike images that show his shifting frame of mind—his and his sister’s sense of desolation in a white room; the feeling of richness, complication, and mystery in a red one. The production design itself creates the meaning, more than the performances, more than the plot.

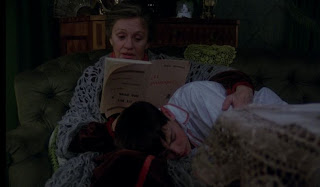

The images in FANNY AND ALEXANDER alternate between stark monotones and vibrant color. Through large sections of the film, Alexander and his sister Fanny are imprisoned in a bleak room, terrorized by their pastor step-father, but there is finally relief in the warm embrace of his grandmother and her extended family.

In Irving Singer’s book INGMAR BERGMAN, CINEMATIC PHILOSOPHER, Bergman is quoted as saying he wanted the film “to move in complete freedom between magic and oatmeal porridge, between boundless terror and a joy that threatens to burst within you.” Singer writes about the film: “The entire plot of FANNY AND ALEXANDER is enclosed within the two ebullient occasions at the outset and the end: one being the Christmas party with its long conga dance of life in which everyone participates, holding on to whoever happens to be in front; the other being the celebration of the birth of two children that includes a dinner served at a huge circular table that looks from above like an enormous halo or festive wreath.”

This image encapsulates FANNY AND ALEXANDER’s theme—life as a banquet of experience, both good and bad.

As I grow older, the films by Yasujiro Ozu have particular resonance for me (there’s too many to name that are among my favorites but here’s a start: TOKYO STORY, LATE SPRING, EARLY SUMMER, EQUINOX FLOWER).

The eloquent final image of AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON–a parent alone, resigned to the inevitable progression of life.

His analysis of family dynamics is unparalleled—he makes the ordinary extraordinary. And he uses places to indicate states of mind: a series of establishing shots will indicate a specific mood; a train shot will indicate transition; a bar will indicate collegiality or loneliness; the home represents comfort and intimacy, and then perhaps isolation.

Bars frequently appear in Ozu’s films, as a place where people commiserate or contemplate. At the end of AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON, a widower stops by for a drink after his daughter’s wedding. The barmaid observes that he’s glum and asks if he’s been to a funeral. He answers, “Something like that.”

I have drawn a great deal of inspiration from Ozu’s work and particularly his use of negative space.

These two images are from the beginning and the end of LATE SPRING. In the first, the man’s daughter greets him as he arrives home. In the second he returns to an empty house after she has married.

There are scenes which are incredibly moving simply by what is not there—a widowed father returns to his home, after he has married off his only daughter, and the house is empty; an empty kitchen door exists where once two sisters-in-law laughed and talked; a man sits at an empty bar where previously he sat with his friends; a man sits at a concert, the seat beside him empty, while the woman he had hoped would join him walks home on an empty street, deep in thought about their missed connection.

In this sequence of shots, a man sits alone at a concert after he has been refused by a young woman. He is juxtaposed with shots of her walking home, wondering perhaps if she’s made the right decision. The fact that the street is empty is significant—it makes the viewer feel something specific about her isolation. Had there been other pedestrians, the character’s inner life would not have come into such stark relief.

Ozu is famous for his establishing shots–shots which capture a mood and suggest an idea. The first of these three is but one of a number of train shots in his many films–it suggests transition, inexorable movement into an uncertain future. The second suggests sadness–a dark, empty house after a daughter has married. The third prominently displays a Coca-Cola sign, suggesting the westernization of the Japanese way of life.

Michael Atkinson wrote about Ozu: “…Ozu’s methodology in LATE SPRING, which became an almost ritualized discipline in his subsequent films, expresses so much more than mere character and narrative: the famous still-life cutaways (themselves a codex of Zen commentaries and signifiers) and tatami-mat-high point of view; the compressed depth of the family’s rooms (Noriko and company pass in and out of sight through doorways we cannot see, suggesting haunting layers of quotidian complexity); the fastidious commemoration of the uniquely careful Japanese living spaces (that no culture has thought as much about the composition and physical meaning of their own homes is not a point lost on Ozu); the vivid manner in which the architectural precision expresses the controlled tone of relationships. There’s an acute sense of home here, happily inhabited, that is unaccented and yet fuels Noriko’s tragedy.”

As I continue to work as a director I find that my focus has shifted more and more to the spaces that the characters inhabit. One could say that it is the actor’s job to exist in the character, and it is the writer’s job to create the story and to give the actors the words to speak, and it is primarily the director’s job to position the characters and story in a space that creates the emotional effect. How does one determine the audience’s point of view and where? Does one use a medium or wide shot, a tracking shot, or a close shot; a horizon line, the sky, a simple room, color or not, or a high-angle looking down upon a character standing on a ledge ringing a bell, like the nun in BLACK NARCISSUS? What story is being told and what are the different effects that the story allows one to find in its environment? As the director Robert M. Young, one of my mentors, used to say to me—“Where’s the story? Put the camera there.” This is my maxim when I direct.

On PRETTY LITTLE LIARS I look for the opportunities to capture the mystery of adolescence.

On GOSSIP GIRL I look for opportunities to emphasize the architecture and romance of New York City.

As much as possible, every image should tell a story. If there are people in the frame, their relative positioning tells a story—are they facing each other or away from one another, separated by distance or touching each other? If there are no people, their absence tells another story.

This is a picture I took of the backyard of my childhood home in 1981, the weekend before we moved, after living there for 23 years. The yard was overgrown and the walls were completely covered with ivy. The house itself was falling apart–the balcony had rotten boards and the roof sagged. But it was such a wonderful place and I still miss it.

If I were to make a film of my own life, the story would start with me sitting next to the rock walls of my backyard—they represent the foundations of my imagination, ideas one upon the next, similar to the construction of the wall, stone by stone.

This is one of my favorite pictures of my dad, standing before the walls he built, next to rose bushes he planted, with one of our dogs and one of our cats. The picture tells a story—the story of a guy who loved to build, who loved to plant, who loved animals. He built spaces that inspired the imagination of his family, particularly this son, and those spaces still exist in my inner world, as vital as many of the films that I love.

Leave a Comment